Urban Green Space and Mental Health Among People Living Alone: The Mediating Roles of Relational and Collective Restoration in an 18-Country Sample

Citation

Pasanen, T. P., White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., van den Bosch, M., Bratman, G. N., Ojala, A., Korpela, K., & Fleming, L. E. (2023). Urban green space and mental health among people living alone: The mediating roles of relational and collective restoration in an 18-country sample. Environmental Research, 232.

More and more people in many developed countries are living alone, especially in cities. While this can offer independence, it often also comes with higher levels of loneliness and poorer mental health. Researchers have suggested that spending time in nature—such as parks and green spaces—might help ease these challenges. Nature can offer chances to connect with other people, strengthen relationships, and feel part of a community, all of which may support mental well-being. However, it’s not yet clear whether these benefits work the same way for everyone.

More and more people in many developed countries are living alone, especially in cities. While this can offer independence, it often also comes with higher levels of loneliness and poorer mental health. Researchers have suggested that spending time in nature—such as parks and green spaces—might help ease these challenges. Nature can offer chances to connect with other people, strengthen relationships, and feel part of a community, all of which may support mental well-being. However, it’s not yet clear whether these benefits work the same way for everyone.

To explore this, researchers looked at 2017–2018 survey data from over 8,000 people living in cities across 18 countries and territories. They compared people who lived alone with those who lived with a partner. Researchers looked at whether having more green space near someone’s home is linked to better mental health, and whether this happens because living near green space leads to visiting green spaces more often and/or feeling more satisfied with personal relationships or with the local community.

Overall, people who visited green spaces more frequently reported better mental well-being and were slightly less likely to use medication for anxiety or depression. These benefits seemed to work partly because green spaces helped people feel happier with their relationships and more connected to their communities. Importantly, these positive effects were just as strong for people living alone as for those living with a partner.

There were some differences in how green space nearby translated into actual visits. For people living with a partner, having more green space close to home generally meant they visited it more often. For those living alone, this link depended on how green space was measured. When researchers looked more closely at people living alone, they found that most patterns were similar across different groups, though the benefits were sometimes stronger for men, people under 60, those without financial strain, and people living in warmer climates.

In short, making it easier and more appealing for people—whether they live alone or with a partner—to spend time in nearby green spaces could be a simple way to support better mental health. Green spaces don’t just offer fresh air; they can also help people feel more connected to others and to their communities.

Abstract

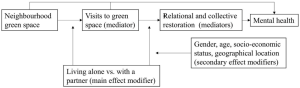

Rates of living alone, especially in more urbanised areas, are increasing across many industrialised countries, with associated increases in feelings of loneliness and poorer mental health. Recent studies have suggested that access to nature (e.g. parks and green spaces) can reduce the stressors associated with loneliness, partly through providing opportunities to nurture personal relationships (relational restoration) and engage in normative community activities (collective restoration). Such associations might vary across different household compositions and socio-demographic or geographical characteristics, but these have not been thoroughly tested. Using data collected across 18 countries/territories in 2017–2018, we grouped urban respondents into those living alone (n = 2062) and those living with a partner (n = 6218). Using multigroup path modelling, we tested whether the associations between neighbourhood greenspace coverage (1-km-buffer from home) and mental health are sequentially mediated by: (a) visits to greenspace; and subsequently (b) relationship and/or community satisfaction, as operationalisations of relational and collective restoration, respectively. We also tested whether any indirect associations varied among subgroups of respondents living alone.

Analyses showed that visiting green space was associated with greater mental well-being and marginally lower odds of using anxiety/depression medication use indirectly, mediated via both relationship and community satisfaction. These indirect associations were equally strong among respondents living alone and those living with a partner. Neighbourhood green space was, additionally, associated with more visits among respondents living with a partner, whereas among those living alone, this was sensitive to the green space metric. Within subgroups of people living alone, few overall differences were found. Some indirect pathways were, nevertheless, stronger in males, under 60-year-olds, those with no financial strain, and residents in warmer climates. In conclusion, supporting those living alone, as well as those living with a partner, to more frequently access their local greenspaces could help improve mental health via promoting relational and collective restoration.